Checksum is an ongoing series of long reads on digital fingerprints and the experience of individuals under surveillance.

Previously: Through the horror films Paranormal Activity (2007) and Unfriended: Dark Web (2018), I’ve discussed how the domestic space has become increasingly populated, and even defined, by digital elements. During the coronavirus pandemic, tech became a necessity for everyday professional and social life, and digital experience became inextricable from domestic spaces. That dependence breeds vulnerability, however, and our susceptibility to digital violence requires the thoughtful investigation of Laura Poitras’ Terror Contagion (2021).

“Surveillance is not only a breach of privacy, it is violence.”

Laura Poitras has spent the better part of her filmmaking career as a target of surveillance from the US government. Her close collaboration with subjects, such as Al Qaeda bodyguard Abu Jandal, NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, has earned her a high threat rating on the Department of Homeland Security’s watchlist. As a result, she has been subject to detainment, interrogation, monitoring, and has been threatened with being refused entry back into the USA. Forensic Architecture, a London-based research group who focus on international human rights violation, frequently study the treatment of targets such as Poitras. After many of their colleagues were hacked using spyware from Israeli cyber-intelligence firm NSO Group, Forensic Architecture began to map a “global landscape of digital infections,” tracking the digital and physical violence directed towards journalists, activists, and dissidents around the world. Poitras joined the project as a collaborator and documentarian, filming the progress of their investigation and observing the world of increased surveillance around her – the result is her short film Terror Contagion.

She begins with interior shots of her office. Her camera focuses on the metal girders of the ceiling and closed windows, defining the enclosed space we are limited to. Only briefly, at first, does she offer up the outside world. Opening a window onto a fire escape, we’re given a glimpse of leaves and air, a brief reprieve from the confines of her building. Yet, on the other side of that expanse of freedom are still more windows, each telling a similar story of captivity. Such was life at the time of filming, with necessary regulations in place to limit the spread of Covid-19. For the majority, domestic life was now an all-encompassing boundary of consciousness and existence.

There’s a sense of apocalypse to the quietude that Poitras paints, scanning the streets outside to find only police cars and a gentle breeze. Nothing immediately threatening is looming in the frame, but the tension of its eerie calm is akin to the still frames of found footage in Paranormal Activity.

NSO Case Studies

The fear and panic associated with that impending doom led to a desire for control – to know where the disease was and whether we were safe. In March 2020, the NSO contact-tracing software ‘Fleming’ was launched, intended to “use cell phone and public health data to identify where people with coronavirus are and who they come in contact with.” This was the first civilian product which could achieve this level of close contact-tracing, and was marketed to health ministries across the world. This is not dissimilar to many other contact-tracing programs adopted by governments at this time, despite serious privacy concerns. In June of 2020, the UK government chose to scrap plans for a centralised model of data collection, acknowledging the danger of storing massive quantities of personal information.

The risk of a central database was exemplified by the discovery of an unprotected NSO database in May of 2020. The database included five hundred thousand location data points for more than thirty thousand distinct mobile phones during a period of six weeks, from 10 March to 13 April 2020.

Denying that this was a security oversight, Oren Ganz, a director at NSO, stated:

“The Fleming demo is not based on real and genuine data. [….] The demo is rather an illustration of public obfuscated data. It does not contain any personal identifying information of any sort.”

However, the data patterns were found to be consistent with real phone activity by mobile network security expert Gary Miller and Senior Researcher at the cybersecurity research group Citizen Lab John Scott-Railton. This breach was a global data crisis, as it violated the privacy of individuals in Rwanda, Israel, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

NSO Group is better known for its spyware ‘Pegasus,’ marketed as a product that can be covertly installed on mobile devices to surveil individuals believed to be involved in criminal or terrorist activities. Its broad capabilities, however, allow governments and private institutions to watch and exploit journalists, political activists and dissidents. The spyware was first discovered in 2016 when human rights activist Ahmed Mansoor received an enticing text message providing a link to “secrets” regarding prison torture in the United Arab Emirates. Mansoor passed this onto Citizen Lab in Toronto, who found that had he clicked the link, the spyware would jailbreak his phone to install itself and collect any and all communication and location data.

From the manual for Pegasus spyware: “Pegasus is a world-leading cyber intelligence solution that enables law enforcement and intelligence agencies to remotely and covertly extract valuable intelligence from virtually any mobile device.”

The argument for such technology advocates a democratisation that moves surveillance power away from government agencies and into the hands of commercial users. Under such a system, the digital elite would no longer hold all the power, and with an off-the-shelf product spyware will be accessible to all. However, this mode of an unrestrained data economy has only consolidated power in the hands of the few. Since 2016, Pegasus has been used in some of the most high-profile cases of government surveillance, including the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi authorities, and the abuse towards journalists by the government of Mexico.

One of the first documented victims of Pegasus was investigative journalist, Carmen Aristegui, who agrees to appear in Poitras’ film and joins a video call interview with Poitras and Forensic Architecture’s lead researcher Shourideh Molavi. Aristegui was one of the first individuals documented by Citizen Lab to be targeted by Pegasus software. In discussing the Mexican government’s treatment of dissidents, Molavi touches on the Iguala mass kidnapping of 2014.

Over a hundred students of the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College were intercepted while allegedly attempting to commandeer three buses for a trip to Mexico City. The students claimed they were in fact hitchhiking at the time. During a roadblock, students were fired upon and many were rounded up into police vehicles before being handed over to cartel organisation Guerreros Unidos. Forty three students were missing and likely dead, allegedly because Guerreros Unidos believed many of the students were members of rival gang Los Rojos.

The authorities claimed ignorance at the time, but a later investigation by The Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) had different findings. The panel found that a combination of conspiring government agencies, including the army, navy and police, were all aware of the students’ whereabouts and treatment. Their version of events was verifiably impossible. “They all collaborated to make them disappear,” GIEI panel member Carlos Beristain told a press conference ahead of the presentation of the group’s final fact-finding report.

The investigation conducted by the GIEI was targeted with multiple infection attempts using Pegasus in March 2016. The primary exploit attempts came from text messages sent to devices belonging to members of the GIEI. These messages included a link, which if clicked upon, would infect the device with Pegasus malware. The domain of the link destination corresponded to one used in earlier exploit attempts, confirming that members of the GIEI investigation were indeed targeted using NSO spyware.

Molavi describes the pattern of surveillance as a domino effect. First the state targets the protesting students to silence their campaign. Next, journalists who cover the story are subject to digital violence. Then, their lawyers who defend them and the freedom of the press. There is seemingly no limit to who can become a target under such an advanced apparatus.

The ability of Pegasus to send a message with such devastating content from any individual’s phone entirely upends autonomy and trust in communication. Mazen Masri, a lawyer suing NSO, describes this phenomenon of surveillance terror as “somebody sitting in your mind.” This also threatens the promise of escape for refugees fleeing oppressive regimes. Physically departing a country can no longer provide respite, as the potential reach of their digital violence is untethered from geographical constraint.

This was also the case in one of the other primary subjects in Forensic Architecture’s investigation: journalist Jamal Khashoggi. In 2018, Khashoggi was targeted by Saudi authorities, resulting in his murder at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Khashoggi fled Saudi Arabia in 2017 and wrote several articles critical of the Saudi government. In response, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman ordered his death.

Pegasus spyware has been found on the devices of several people close to Khashoggi, including an exploit attempt of his wife Hanan Elatr in 2017. “Jamal warned me before that this might happen,” Elatr said. “It makes me believe they are aware of everything that happened to Jamal through me.” She believed that by accessing the microphone of her device, they were able to monitor his activity.

Omar Abdulaziz was a collaborator of Khashoggi’s, who similarly believes the Saudi government used Pegasus to gain information through their conversations. Abdulaziz was also a harsh critic of the Saudi government, who became a permanent resident of Canada in 2017. In 2018, Abdulaziz received a message regarding a recent online purchase of protein powder, offering a link that would direct him to a package tracking service. Strange events followed, including the arrest of siblings in Saudi Arabia. “I had been wondering why they would jail them, they are not even involved in political activity,” he told the Guardian. He was also in regular contact with Khashoggi regarding a project to tackle online Saudi trolls, in which they planned to distribute sim cards in order to create an opposing army of Twitter users who could effectively challenge online propaganda. In doing so, Khashoggi was now considered a dangerous activist, and thus targeted with direct physical violence.

Screenlife

Throughout Terror Contagion, Poitras utilises Screenlife techniques to bring her digital interface to life. Akin to Unfriended: Dark Web, the action of a shot can be entirely contained within the boundaries of the screen. Very quickly, we are drawn into this structure of images, as Poitras places her tripod in front of her screen, building a bridge between the traditional documentary style she employs in the film’s opening and the new domestic space of the screen. Windows are repositioned and the individual squares of her video calls each contain a world of their own. The video calls are the backbone of Poitras’ collaboration with Forensic Architecture, and by extension with all other journalists and dissidents who want to document and challenge NSO Group’s surveillance and violence.

Conforming to this cyber style, talking heads are presented through the cropped cell of the video call, while their name, job and location are presented in plain text and separated by an underscore. Reinforcing the growing significance of digital selves, their position as an avatar is reconfigured from the subject of surveillance to a collaborator in its resistance. Forensic Architecture and Poitras are largely focused on the vulnerabilities of technology to advanced spyware. Yet the cameras and microphones that are co-opted for nefarious means are equally fundamental to dissidents’ cooperation.

Forensic Architecture utilises this culture of collaboration to discuss the implications of individuals’ experience under surveillance. The focus of their project is to physically map the digital and physical attacks upon dissidents and journalists like Carmen Aristegui and Jamal Khashoggi.

This mapping, parallel to their video interviews, occurs in an entirely digital space. Their plotting begins as a straight-forward chronology to track both digital and physical incidents. Without the opportunity to explore the real-world events as they occur through traditional verite style, such digital approximations as these are essential to provide a visual representation of their extensive investigation.

This timeline for Mexican journalist Carmen Aristegui covers the digital exploit attempts she has been exposed to. Their increasing frequency illustrates a period of intense surveillance by the Mexican government. Layered over this are the corresponding red markers of physical violence, ranging from intimidation to assault to murder. Poitras supplements one of these incidents with security footage of a breakin from Aristegui’s newsroom. The mp4 file is displayed in a separate window, employing the same screenlife apparatus as Unfriended. By moving between different forms of digital media, Poitras connects the collaborative communication of their video calls to the diagrammatic representation of their investigation and the evident footage of corresponding physical violence.

Forensic Architecture’s data map not only exhibits all people who have been attacked by NSO software, but includes the corresponding nation states responsible for their persecution. Correlating political events are then plotted on a separate axis, adding another plane of information to the graph. Poitras’ exploration of this weightless digital graph moves amongst the floating lines and colours, transforming the flat chronology into an interactive experience. The three-dimensional abyss the event markers inhabit has a potential endlessness, enforcing the unlimited threat of surveillance. Each line assigned to a specific subject could theoretically continue into the horizon, and lines multiply as the investigation continues, creating a boundless proliferation of data. The lateral shots of the timeline in particular create an imposing presence of the threatening red spheres, as they creep closer to the digitised camera, not unlike the foundational cinematic terror in The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1896).

Moving out to a holistic view of the plotted data, Forensic Architecture constructs a vast audiovisual presentation of digital and physical violence. The overlapping lines and competing lights that populate the axes illustrate the web of chaos found in the empirical evidence of surveillance.

Spyware Localisation

While Forensic Architecture’s investigation plots the complex network of the use of Pegasus in at least 45 countries (according to Citizen Lab’s findings), Poitras seems equally concerned about smaller scale surveillance.

Poitras has herself been a victim of aggressive surveillance by the US government. In a voiceover, she discusses her experience with Edward Snowden, as documented in Citizenfour (2014). Her initial contact with him was a watershed moment where a veil was lifted upon the NSA’s surveillance practices. Following the espionage and intrigue of that time of her life, she questions who she can trust and who may be targeting her. Poitras is therefore uniquely positioned as both a victim and an activist, who can cast a perceptive and watchful eye over state surveillance.

Her external shots focus largely on the seemingly quotidian activity of police officers. While the frame contains very little movement, reds and blues permeate throughout. Officers walk back and forth without any particular goal in mind, but just like their colours, the world around Poitras is fully saturated in police presence.

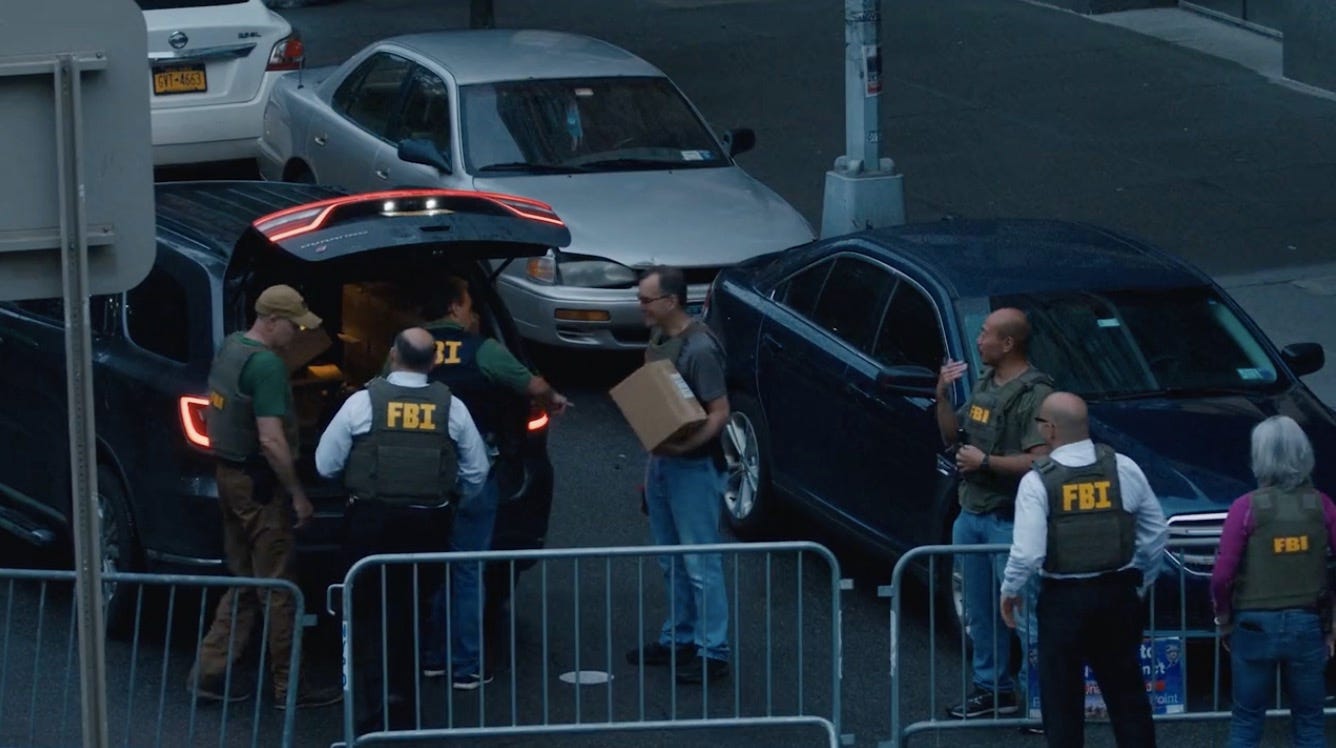

Further shots show the NYPD receiving tactical gear from the FBI. Poitras calls this into question, asking why state police require such advanced material. Particularly at a time of relative civil calm at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, the necessity for an operational capacity akin to federal agencies seems implausible. However, Poitras’ focus on the NYPD explores the possibility that tech devolution has allowed a trickle-down effect of nation-state level weapons.

Poitras then maintains a stationary shot of a Black Lives Matter march moving down the street, immediately juxtaposed with police bikes, presumably mobilised to attend to the march. While protesters are merely armed with signs, the police appear armoured and equipped with riot shields. By holding the same static angle, Poitras presents the seemingly endless convoy passing across the frame like a clown car of cops. The adjacent examples suggest the tactical gear provided by the FBI was intended for the control of potential civil unrest such as this, ramping up the tension between peaceful protestors and an increasingly heavily-equipped police force.

NSO did in fact attempt to sell nation state level cyber weapons to local police in the US. In 2016, Westbridge Technologies – the North American branch of NSO Group – presented a phone hacking technology known as ‘Phantom’ to the San Diego Police Department (SDPD). “Turn your target’s smartphone into an intelligence mine,” the brochure reads. Following remote installation, Phantom is capable of extracting message and location data, as well as accessing the device’s microphone and camera. In practice, this spyware would be no different than Pegasus. The only difference would be its geographical concentration of use. Rather than, for instance, hacking thirty thousand devices across four nation states, Pegasus (or its equivalent brand name) could be used within the jurisdiction of a single police department to track petty crime and ‘suspicious’ activity. This would also be dictated entirely by a state institution’s relationship with a private company, rather than controlled through federal regulation. The potential implication here is that depending on what side of a jurisdiction line you fall on, your privacy could be entirely eroded by a single purchase.

However, the ethical questions around this were not the reason for the SDPD’s lack of investment in Phantom. Sergeant Meyer responded to Westbridge Technologies, saying “we simply do not have the kind of funds to move forward on such a large scale project.” The only obstacle to the dissemination of spyware into the hands of local police is therefore financial – an easily traversable obstacle.

On a wider scale, the federal US government has had a fraught relationship with NSO Group. In March of 2023, the Biden administration passed an executive order that seeks to prevent the government’s use of commercial spyware. In 2021 NSO had been blacklisted by the USA, although just two years earlier the FBI confirmed it had procured a licence for Pegasus for the purpose of “product testing and evaluation only,” and “there was no operational use in support of any investigation.” However, according to a New York Times report, NSO did conduct a demonstration of what was presented as ‘Phantom’ to the FBI in 2019, involving an alleged attack on a US mobile device.

NSO has also drawn ire from private companies. In 2019 WhatsApp filed a lawsuit alleging the transmission of malware to 1,400 users. WhatsApp also accused NSO of targeting a US mobile device in 2019, which appears to be the same instance as their demonstration of Phantom to the FBI. In the case of the former accusation, NSO argued that the alleged malware fell under the responsibility of the nation states deploying their spyware, and they are themselves not responsible for the misuse of their technology. There is therefore significant judicial and legislative backlash to the introduction of NSO technology in the US, yet their lack of culpability only further demonstrates the nebulous tumult of spyware’s global capabilities.

As Poitras continues her observational camerawork, police officers begin to notice her watchful eye. One officer looks up at her for a short while before pulling out his flashlight and aiming it into the lens. His hope is presumably to deter her from any further filming. Yet the image is a valuable encapsulation of encroaching surveillance. Poitras herself is not disturbing the peace in any way, merely aiming her camera into the street. The officer’s primary objection is that he is the subject of her view. By using his flashlight, he seeks to both illuminate her, and obscure himself – to keep the public under harsh lights, and the police in the shadows.

The film concludes with one of the most consistent and powerful motifs in Poitras’ career – watching the watchers. In a drone shot, her camera moves slowly over a horse-shoe shaped building identified as the NYPD counterterrorism centre. The central courtyard below reveals a space within the walls of security. Its structure betrays a fear of invasion from unwanted eyes, the very same invasion pushed forward by their flirtation with advanced spyware like Pegasus. The vulnerability of this open space within gives Poitras brief access to find frailty from above. In merely casting an eye over these pillars of surveillance, Poitras is able to reduce the buildings to glass, concrete and stone, and make fallible their potential threat.

The dependence upon, and resulting vulnerability to, digital devices is starkly illustrated in Forensic Architecture’s case studies of Carmen Aristegui and Jamal Khashoggi. The violence levelled towards them and those close to them only reifies the importance of investigative journalists like Poitras to illuminate the most pressing issues of surveillance through documentaries such as Terror Contagion.

This is particularly true when surveillance has become a commercial venture. No longer is the NSA’s shadowy bureaucratic apparatus required; users will purchase Ring cameras to record their every move, the FBI will conduct drone and satellite surveillance in plain view, and local police will have access to the most invasive digital weapons in the world for the low, low price of privacy.